May 24, 2025

The Straits Times – Sun, sand and saving the planet?

Read the original story on The Straits Times.

With marine and coastal tourism being a major part of the ocean economy, Insight looks into its role in helping communities earn a living, while protecting nature.

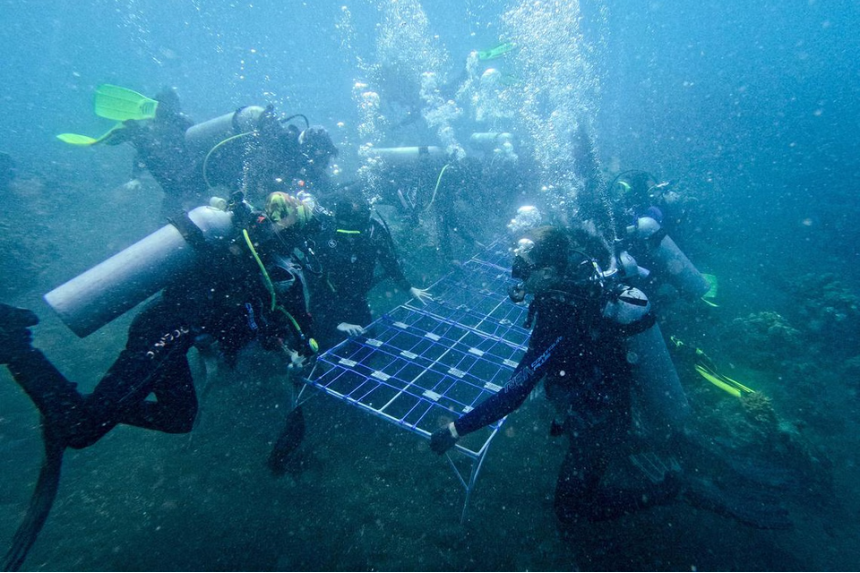

A group of students taking part in coral planting, one of the activities organised by the social enterprise Sea Communities in Les, Bali, on Sept 25.ST PHOTO: AUDREY TAN

SINGAPORE – They have scuba-dived in many parts of Asia, from the reefs of Manado, Indonesia, to the mysterious depths of Yonaguni, Japan.

While on the Indonesian isle of Bali last September, the Chua family – Amanda, 37, her brother Irwin, 33, and their cousins Gabriel, 28, and Zachary, 20 – embarked on a new underwater adventure: planting corals with Livingseas, a dive centre in Padangbai town.

The coral restoration programme ropes in tourists to help bring life back to the seafloor, left barren after the original reef had been destroyed by blast fishing, a fishing practice involving the use of explosives to stun or kill large schools of fish.

For a fee of around $200 a person, tourists can go diving to help install artificial reef structures, known as reef stars, on the seafloor, with baby corals attached to them using cable ties. At the same time, they can learn more about coral reefs – tropical habitats that cover less than 1 per cent of the global seafloor.

The fee goes towards restoration efforts and also covers costs of equipment rental and dive guides.

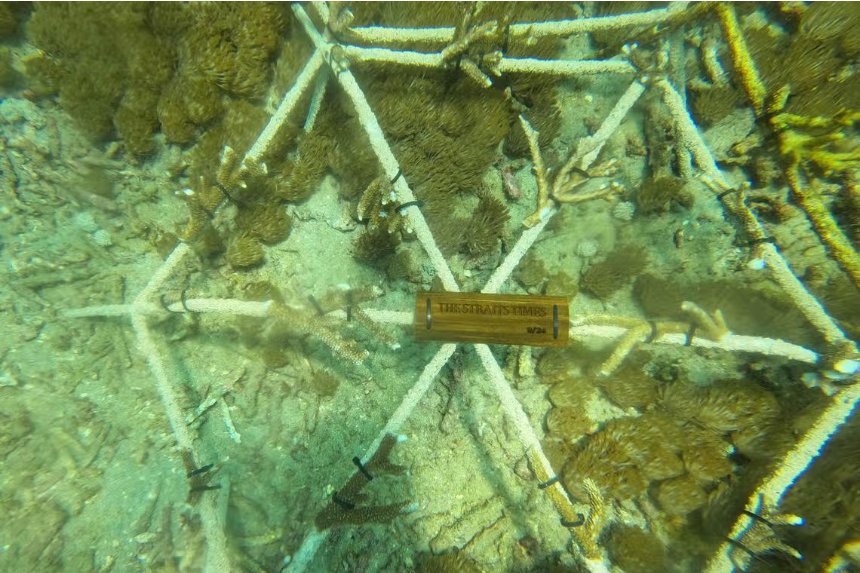

In September 2024, assistant news editor Audrey Tan installed The Straits Times reef star at a dive site in Padangbai, Bali. It is now part of the growing reef. PHOTO: LIVINGSEAS ASIA

Over time, the coral fragments will grow, covering the original structure and recruiting a greater diversity of coral and fish species.

Said Mr Gabriel Chua, an entrepreneur:

“We joined the coral restoration exercise out of a deep love for the ocean. Over the years, we’ve watched some of our favourite dive sites decline, and it made a real impact on us.”

He added: “This felt like a meaningful way to give back to the underwater world that has given us so much.”

Clockwise from top left: The Chua family – Gabriel, Amanda, Zachary and Irwin – took part in a coral planting activity at Livingseas in September 2024.ST PHOTO: SAMUEL RUBY

The Livingseas coral restoration experience is part of the marine and coastal tourism sector, which has been a major contributor to the global ocean economy, found a March report by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

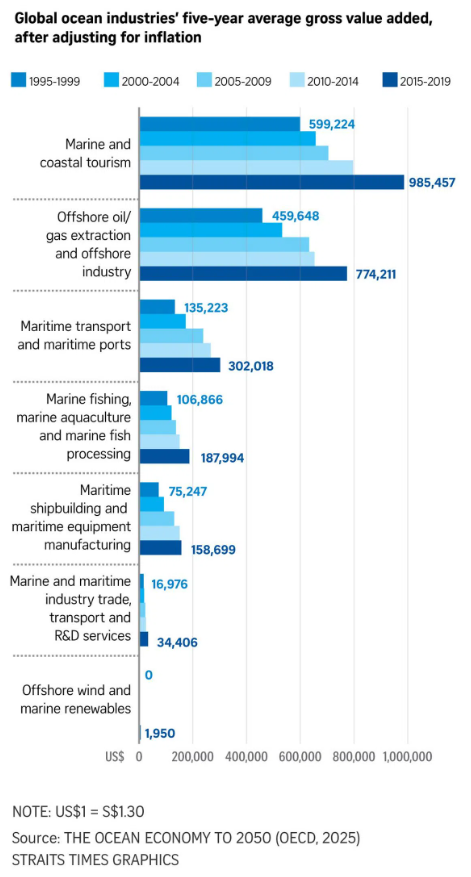

The ocean economy – which also includes the maritime, energy, aquaculture and fisheries sectors, among others – doubled in real terms from US$1.3 trillion (S$1.68 trillion) of gross value added in 1995 to US$2.6 trillion in 2020. That would make the ocean the world’s fifth-largest economy in 2019, if it were a country.

Of the seven ocean sectors analysed in the report, the two largest economic activities between 1995 and 2020 were marine and coastal tourism and offshore oil and gas extraction, which together generated two-thirds of the total gross value added.

Gross value added generated by marine and coastal tourism reached a high of US$1.06 trillion in 2019, before falling to US$910 billion in 2020 due to Covid-19 restrictions. Offshore oil and gas and offshore industry peaked at US$987 billion in 2020.

Titled The Ocean Economy To 2050, the report also highlighted the importance of ensuring the marine realm remains healthy, so the ocean can continue to buoy up the many economic sectors reliant on it.

But ocean perils are numerous, spanning local threats like destructive fishing practices and pollution, to global ones such as climate change and marine heatwaves.

Tourism can sometimes provide alternative livelihoods for communities, so they are able to carry on using the sea as a resource without damaging it.

But some ventures have also been associated with environmental damage, when tourists get too close to wildlife, destroy habitats, or pollute the environment.

Ahead of the third UN Ocean Conference, which will be held from June 9 to 13 in Nice, France, with the aim of discussing how the oceans and marine resources can be conserved and sustainably used, Insight explores the role of eco-tourism in protecting South-east Asia’s coastal ecosystems from local menaces.

In seeing the world, can tourists help to save the planet – by preserving nature and also by supporting the livelihoods, culture, and well-being of the communities who call the coast home?

What makes an eco-tourist?

There is no single definition of what it means to be an eco-tourist.

As Ms Elaine Kwee, who co-founded social enterprise Sea Communities in 2012, said: “Eco-tourism is one of those terms that give you a warm, fuzzy feeling, but can mean anything to anyone.”

A hotel, for example, may label itself an eco-destination for changing the linens once every three days instead of daily. Holiday-makers may consider themselves eco-tourists for simply being out in nature.

“There is no legal definition,” said Ms Kwee, 58, a Singaporean and former corporate finance lawyer. “But I’d like to think that our programmes attract tourists who want to learn about the coastal environment and the local communities.”

Sea Communities is an Indonesian enterprise that creates employment and income opportunities for the local community through its eco-tourism programmes. Since 2012, it has been working with Les Village in north-eastern Bali to conduct educational programmes, including coral restoration, for groups from universities, boutique travel agencies and special interest organisations all over the world.

The revenue from such activities reduces the need for fishermen there to turn back to their former livelihoods – fishing for ornamental fish with cyanide, a poison that was used from the 1980s to the early 2000s.

The sustained use of the toxic substance ended up destroying the reefs in the waters near their homes.

Reef rehabilitation programmes involving tourists and scientists from Singapore are now ongoing at Les.

Tourists gain a unique experience – planting corals – but more crucially, the money they spend on it helps ensure the continuation of the restoration efforts, Ms Kwee said.

“It is the fishermen who need to dive regularly to do coral maintenance, to renew the plantings if some coral babies die… tourist dollars help to fund the tanks and the diving for the community”, she said.

Marine biologist Sam Shu Qin (left) and Made Merta, affectionately known as Pak Eka, observing a coral nursery in Les, Bali, on Sept 25, 2024.ST PHOTO: AUDREY TAN

Ms Kwee said Sea Communities uses a business model that ensures the revenue is distributed evenly throughout the community, not just among the fishermen.

“We cost up – whatever the home stay charges, whatever the fishermen charge, whatever the salt farmers charge, we put that into the price, and then we charge something extra for arranging the educational programmes and logistics. We don’t try to capture all the wealth at the top,” she said.

“It’s more motivating and incentivising for the local community to see that conservation can make their livelihoods better.”

When Sea Communities introduced the concept of eco-tourism to the community in 2012, a former ornamental fish trader known in the community as Jro Bau – his real name is Mr Gede Yudarta, 65 – sold his car to build five villas for tourists.

Mr Gede Yudarta, also known as Jro Bau, owner of Les Homestay, with his wife Made Srestiandnyani, who manages the on-site restaurant, in Les, Bali, on Sept 23, 2024.ST PHOTO: SAMUEL RUBY

When tourism took off, Jro Bau built 11 more villas, while his wife Made Srestiandnyani, 48, opened a restaurant in the village in 2015. Today, her kitchen is even equipped with a pizza oven, she said, and the kitchen crew – all women from Les Village – are able to whip up all sorts of dishes, from Indonesian delights to hamburgers.

One of the air-conditioned chalets established to welcome tourists taking part in the village’s eco-tourism activities, including coral planting.ST PHOTO: SAMUEL RUBY

During the peak season for tourists, which is usually between May and August, as well as from September to early December, Sea Communities conducts tours for about three to four big groups of 20 to 60 guests every month, said Ms Kwee.

At Livingseas, its Singaporean founder Leon Boey, 45, said the coral restoration experience it offers differs from regular dive trips in Bali.

“When you go diving to see manta rays, you go down, float around, and enjoy the view,” he said. “But when you are planting coral, it is not you looking at the fish, but sometimes, the fish looking at you. You’re not just taking, but giving back, in a way.”

Livingseas started out as a dive centre based in Sanur, Bali, in 2011, conducting diving courses and offering dive trips to many popular sites around Bali, such as to Manta Point where manta rays are regularly sighted.

In 2016, it moved its operations to Padangbai – about an hour’s drive from Sanur. When the Covid-19 pandemic hit and tourism ground to a halt in 2020, Mr Boey said he started experimenting with reef restoration in the area, to try to help the local reef recover from the blast fishing.

Since then, the endeavour has grown, with over 80 per cent of the dive centre’s revenue coming from its coral restoration programme, he told The Straits Times.

Prices start from 650,000 rupiah (S$51) per person for a half-day snorkelling experience. Scuba divers can also “plant” a reef star with a personalised bamboo tag for about 2.5 million rupiah, which is inclusive of two dives.

His team has also grown, from a small crew of three to now almost 35, many of whom are local youth.

“We scaled up because of the restoration, and because of the tourism income, we trained them to dive, we trained them in coral restoration, and many of them are moving on to become divemasters who are certified to lead dives,” Mr Boey said.

Currently, about 98 per cent of the 100 to 200 guests that Livingseas receives every month opt for the coral restoration activities, instead of regular diving, Mr Boey said.

Livingseas’ aim is to cover 5ha of the degraded seafloor – slightly larger than the size of the Padang in Singapore – with artificial reef structures. Currently, about five years into the effort, about 10 per cent of the target has been achieved, according to Mr Boey.

He said: “Before we started restoration, the place was pretty much a barren desert. Most of the coral reefs had been destroyed, and the seafloor was mainly rubble.”

The ecosystem is being rebuilt slowly but surely, with small fish to larger animals, such as sharks and turtles, spotted in the regenerating reef. Dolphins, too, have been spotted near the restoration site.

This has made an impact on the community, said Mr Boey. “The village knows there’s a lot of benefit from the reef restoration, from changing destructive fishing practices, and generally, having more mindfulness about the ocean,” he added.

Mr Boey said that Livingseas did an impact study which showed that in 2024, more than US$270,000 from guests flowed into the village for accommodation, food, and transport activities.

This represented the yearly income of about 108 local families, or about 13 per cent of the total number of families living in Padangbai, he added.

The ocean and the economy

The vast ocean can seem too big, too remote, and too unrelatable for many.

Yet, it is the backdrop against which the theatre of life carries on, affecting how goods from around the world are transported, providing the ingredients for many an omakase dish, and hosting the many urbanites who seek solace and “vitamin sea”.

The ocean also generates 50 per cent of the oxygen people need, absorbs 25 per cent of all carbon dioxide emissions and captures 90 per cent of the excess heat generated by these emissions, according to the UN.

The OECD report pointed to the mounting pressures on the ocean, including from climate change and overfishing, and highlighted the importance of ensuring the ocean remains healthy, if countries are to continue reaping economic benefits from it.

“Successfully developing a resilient and more productive ocean economy will depend largely on the world’s ability to control climate change and mitigate its worst effects, by enhancing biodiversity conservation, sustainable use and restoration as well, and harnessing the expected transformation of the global energy system,” the report said.

The publication comes at a time when the private sector is also starting to take stock of the value of the ocean.

As Dr Alfredo Giron, the head of ocean at the World Economic Forum, told The Straits Times in the Green Pulse podcast: “In the past, we focused a lot of our attention on caring about the ocean for the sake of the ocean, the sake of the animals, the sake of the ecosystem health, and not so much linking it to why it also matters to people.”

He added: “And that is a key thing – we need to start thinking a little bit more about the concept of prosperity, not only the concept of nature and conservation, (but also) about food security, jobs, energy, even recreation and cultural values.”

Philanthropists also see that eco-tourism has a role to play in helping communities earn a living in a sustainable way.

Ms Carol Liew, the managing director of ECCA Family Foundation, which has an office in Singapore, said the foundation supports a small but growing number of eco-tourism initiatives, primarily in South-east Asia.

These include a Sea Guardians project in Thailand, which aims to empower local fishing communities as stewards of marine conservation through the creation of locally managed protected areas. Alternative livelihood models, such as eco-tourism, are introduced to reduce over-reliance on activities like fishing.

The region offers significant opportunities for eco-tourism due to its vast and diverse coastlines, coral reefs, and natural ecosystems, Ms Liew said.

“Many local communities depend on natural resources, and tourism – when done right – can offer an alternative livelihood that incentivises environmental protection,” Ms Liew added. “The region also holds deep cultural connections to nature, which can enhance the authenticity and resilience of eco-tourism efforts.”

However, the foundation also assesses the ventures it supports to ensure the tourism activities are not associated with environmental damage.

Some of the red flags it watches out for include tourism models that drive overdevelopment or degrade ecosystems from unregulated boat traffic or coral trampling; projects that shift control away from communities; and greenwashing. Such practices can include the use of eco-labels without accountability or long-term conservation outcomes.

Identifying good eco-tourism practices

While there is the potential for reef restoration activities to be integrated with tourism ventures, one marine scientist said it is important that tourists learn more about the reasons for the restoration.

Dr Jani Tanzil, a coral reef scientist and the facility director of the St John’s Island National Marine Laboratory, said: “I’ve seen some places where the natural reef is growing very nicely, but artificial reef structures are still installed, squashing all the recruiting corals.”

Even if a reef is degraded, it has the capacity to regenerate naturally, and it is important that this is assessed before active restoration efforts are launched, Dr Tanzil said.

“My take is that if there has been no natural recovery for a very long time, then active intervention is justified,” she added.

Regardless of this, she noted that there are intangible benefits to coral restoration, such as raising awareness of these habitats, and educating people on their importance.

“We do need to convince people that coral reefs are worth protecting, but it’s hard to create that emotional awareness with numbers and facts. People can’t love what they don’t know,” Dr Tanzil said.

Coral restoration as an eco-tourism activity is a double-edged sword, she acknowledged.

Tourists can help by being more discerning about the activities they join, she said – they can ask themselves why restoration is needed, whether the coral restoration activities are guided by scientific advice, and whether local communities are engaged and benefiting from the enterprise.

They should also find out the source of the coral fragments used for restoration, and whether the restored corals’ survival rates are tracked, she added.

At Les Village, Singaporean marine biologist Sam Shu Qin, a lecturer at NUS College, provides scientific advice to the coral restoration effort.

“We want to find out the best methods and strategies to grow corals here in Les Village, and to find out the methods that the local communities can use,” said Ms Sam. “It has to be an accessible method, so that the community can eventually scale up the restoration on their own.”

Ms Sam said that the scientists also share with the community the various scientific methods of assessing the health of the reef over time.

“Eventually, we hope that they develop the skills to protect and then take care of their own reef,” she added.

Ms Kathy Xu is the founder of Dorsal Effect, an eco-tourism enterprise that enlists shark fishermen in Lombok, Indonesia, to take tourists out on shark-spotting tours instead.

She said that the concept of eco-tourism is gaining popularity, especially with many people on social media endorsing the benefits of engaging in nature-related activities while on holiday.

Excessive tourism is a real threat, she said, as large numbers of tourists can cause a lot of environmental harm.

“Travellers need to be more discerning, but also more willing to part with their money to pay the premium, that will go directly to local communities and wildlife, to ensure these communities are empowered,” she said.

“Avoid mass tours, do your research before travelling, and be willing to spend more on legitimate eco-tourism outfits,” Ms Xu said, adding that tourists can also consider taking less emissions-heavy forms of transport, such as trains instead of planes, or going vegan, to reduce their environmental impact.

Ultimately, it is everyone’s responsibility to take care of his or her own impact on the environment, rather than just rely on the claims of an operator, she added.

Ms Ni Luh Andari Widya Lestari, 31, from Les Village, is the Sea Communities ground manager who coordinates the tourism activities. For her, eco-tourism demonstrates “pure heart in doing work for the environment, and for the community”.

“It’s not just about the environment, but also (about) humans,” she said.